Considered highly experimental at the time, December 2009 sees the one hundredth anniversary of the opening to the public of the Manhattan Bridge. Although it has survived a century the design, construction and maintenance has been no walk in the park thanks to something called deflection theory.

A hundred years ago, the citizens of New York were in an anticipatory mood. After eight years of planning and construction the third and last suspension bridge – the Manhattan - to cross the lower East River was nearing completion and would open for traffic on 31 December 1909. The bridge is still there, one hundred years later. Landmark, film and TV star, popular place of suicide but still above all a fantastic piece of early twentieth century engineering the bridge has seen many a President come and go but remains one of New York’s most treasured edifices. Although it has often been overshadowed by its more elegant and famous neighbors, let’s take a look at the life and times of the Manhattan Bridge.

The preparatory work on the bridge started in 1901. The bridge has had a troubled history over the years and this began at the design stage. The intention was to relieve the huge amount of traffic going over the Brooklyn Bridge and the Manhattan Bridge would, ultimately, be damned by its own success. The Commissioner of the New York City Department of Bridges (they didn’t do acronyms then half as well as we do), Gustov Lindenthal’s first design was thrown out purely for reasons of aesthetics. He came back with another idea – incorporating two thin-profile steel towers. This idea was retained but his main plan – four cables made of immense chains of eye bars (lengths of steel at least ten foot long joined at each end by steel pins) was again rejected. Perhaps the thought of what was essentially a gargantuan bicycle chain put the chills up the spine of the city fathers.

1904 saw a new mayor and, with him, a new bridge commissioner. Enter Leon Moiseeiff a bridge designer with many ideas before his time. His design was a suspension bridge as well band it was to keep the idea of the thin towers. However, it got rid of the idea of the bicycle chain bridge by suggesting steel wire instead. Most critical in difference, however, was Moiseeiff’s adherence to a bridge engineering principle that was astonishingly modern and new – a principle known as deflection theory.

Deflection theory supposed – and still does – that suspension bridges are in fact much stronger than they seem, on paper, to be. To a modern readership, a Google search for deflection theory will get results as much about the seduction of women as the building of bridges, but this is a usurpation of its original meaning. The theory was first put across only in 1888 – and technology did not move along quite as quickly then as it does today so in the first decade of the twentieth century it was still a dazzlingly new concept. The theory held that suspension bridges did not need the enormous stiffening trusses used on the like of the Williamsburg Bridge just down the river.

The ideas were brilliant – and the design was adopted. However, as with any theory, steps are made to its perfection by a system of trial and error. The Manhattan Bridge was, unfortunately, to become one of those errors. In fact, deflection theory was not to be perfected for decades. What this ultimately means is that the Manhattan Bridge – although massive, huge, enormous – any number of adjectives can apply – was effectively underbuilt. It could have been worse, of course. Moiseeiff later went on to design the infamous Tacoma Narrow Bridge in Washington. It opened in July 1940 and collapsed in November of the same year. Although no people died it did claim the life of a Cocker Spaniel called Tubby.

Not that the Manhattan Bridge was without its own extremely serious problems. Moiseeiff and his fellow designer Ralph Modjeski put the subway and streetcar lines on the outer edges of the roadway. The streetcar lanes – by general desire – were replaced by car lanes after the Second World War but it was the decision to place them at the edge of the roadway that was to cause the problems. As the trains and cars inexorably moved across the bridge, their load placed an unending and serious twisting strain on the deck of the bridge – which was only lightly reinforced. This meant continual headaches for maintenance crews and eventually – in the 1980s – a long term reconstruction plan was finally put in to place. It ended in 2007 which only goes to show the problems that had to be overcome.

Still, the bridge held and stood its ground. People never fail to be impressed by the stone archway which serves as the entrance to the Manhattan side. The Brooklyn approach is – without a doubt – less impressive and grand. In fact, the original statues, bronze allegories of Brooklyn and Manhattan, were dismantled in the sixties so that traffic flow could be improved. They can still be found in the Brooklyn Museum.

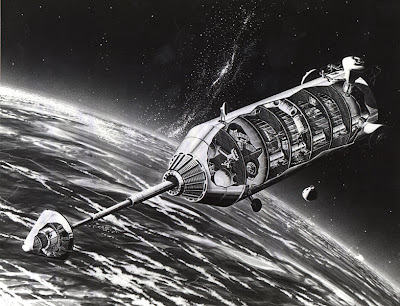

Image by author

Image by author

The bridge spans 1470 feet and links the Bowery and Canal Street with Flatbush Avenue. Gentrification near the bridge – and let’s face it, what a view - has introduced another acronym to the world. Once known as Fulton Landing the neighborhood is now known as DUMBO – Down Under the Manhattan Bridge Overpass. Perhaps, though, because of its association with suicide, the pedestrian walkway was closed down in 1941 and did not re-open till 2001. This walkway was also used by cyclists until 2004 when a dedicated cycle path was introduced. These are, of course, in addition to the four vehicle lanes (two going each way) placed on the upper level and the four subway tracks (ditto) on the lower.

The arches under the bridge are as impressive as what lies above. Wondering what happened to Lindenthal – the spurned engineer? He maintained a huge grudge against the mayor and the designers throughout the construction of the bridge and lost no time criticizing, whenever he could, the overblown budgets, political corruption and delays endemic during that particular administration. Mayor McClellan, eager to proved him wrong, ordered work to be stepped up – some might say rushed. However, the four main cables were spun over the river in just four months. And the budget? Although it seems tiny by our own financial excesses, the original cost of building the bridge has been put at thirty one million dollars.

On the opening day, 31 December 1909, Mayor McClellan and his entourage were to progress – symbol of the patrician class of New York – grandly across the bridge. Unfortunately, the roadway wasn’t finished so they had to get out of their cars and walk the final one hundred yards. At least one person had dies – quite gruesomely – in the construction of the bridge. Remember poor John McShane – if and when you cross the bridge. In early April 1909, compressed air escaped from a pipe powering a riveting hammer escaped and struck him full on. He was blown clear of the bridge and plummeted one hundred and twenty feet to his death – ironically in to the contactor’s yard.

Although often overshadowed by the Brooklyn Bridge, the Manhattan has had roles in many famous movies too. It is featured heavily in Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America and featured in the hugely successful Ghostbusters. Peter Jackson’s 2005 remake of King Kong also features the bridge as does the Will Smith vehicle I Am Legend. Its reputation for being a favorite spot for suicide attempts has Steve Martin meet Judith Ivy on the bridge in 1984. So, although not as famous as its neighbor, the Manhattan Bridge still has allure. Robin Williams’ character in The Fisher King lives below the bridge on the Brooklyn side.

Sometimes considered unlovely and often overlooked, happy one hundredth birthday to the Manhattan Bridge.